How the West Was Won: The Epic Story Behind Hollywood’s Cinerama Masterpiece

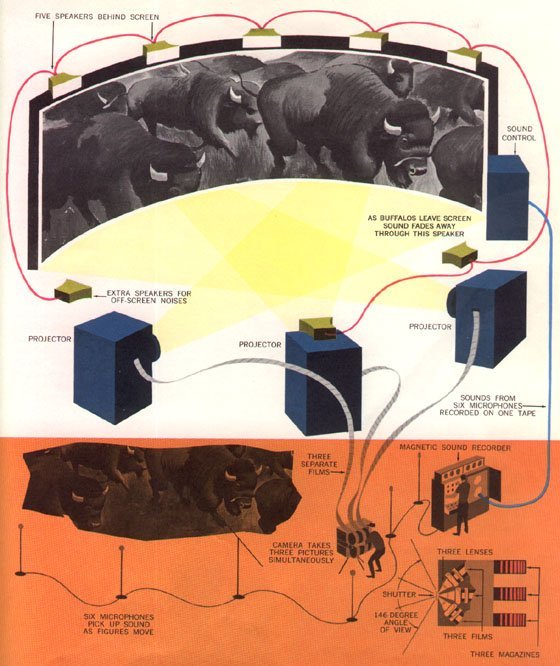

Released to great fanfare in 1962, How the West Was Won is an American epic and the first feature length narrative film produced in the elaborate Cinerama process.

In the late fifties and early sixties, Hollywood studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer sought to bring audiences lost to the rise of television back to theatres with ever increasing spectacle on the big screen. Perhaps the zenith of these efforts was 1959's Ben-Hur, a three and a half hour period piece shot on 65mm film and costing upwards of $15 million. That gambit had paid off handsomely with a box office gross of nearly $150 million and a record eleven Academy Awards – a glowing reception from both the public and critics. MGM was on the hunt for more epics, and found a suitable one in a series of photo essays about the Old West in Life magazine bearing the title How the West Was Won.

As it turns out, the film rights to the story of America's great westward expansion in the 19th century had already been purchased from Life by Bing Crosby, who intended profits from the project to go to St. John's Hospital and had already produced a record on the theme. MGM bought the rights from Crosby, and the promise that profits would go to the Hospital enabled the studio to sign several big name stars to the project for much lower than their usual fees.

The studio envisioned a multi-generational epic spanning a fifty year time period, with an all-star cast made possible by an episodic story structure that would see various characters come and go over the course of the narrative. The studio had signed a contract with the Cinerama corporation to produce four narrative features in the process, and How the West Was Won was selected to be the first.

As the large production entered into the planning process, it became clear that to finish principal photography in time for the film to debut per the contract that large portions of the film would need to be shot simultaneously. So the narrative was split into five segments: “The Rivers”, “The Plains”, “The Civil War”,“The Railroad”, and “The Outlaws,” and each segment was planned and produced like its own film. Three directors were brought on to helm the segments, each one a storied veteran of Hollywood. As producer Bernard Smith said, “We wanted three old pros, no young geniuses.”

Henry Hathaway directed the majority of the picture, helming the “Rivers”, “Plains”, and “Outlaws” segments. Hathaway had been working in the film business since he was ten years old in 1908, and was thirty years into his career as a feature film director when he joined How the West Was Won. Hathaway had overseen Randolph Scott's rise to fame in a series of westerns in the 1930s, and was a favourite of Gary Cooper. He was also used to experimental film processes, having directed the first three-strip Technicolor film shot on location back in 1936. However Hathaway found the shooting process for Cinerama frustrating. The panoramic frame meant he couldn't frame actors any closer than from the waist up, and it was difficult to get natural performances from the cast in front of the large and intrusive camera rig.

Legendary director John Ford helmed the “Civil War” segment, which began filming in March of 1961. Ford is regarded as one of the most important and influential directors of the Golden Age of Hollywood, with four Academy Awards for Best Director across a career of over half a century. Ford worked in many genres, though it is perhaps his westerns that are the most beloved: Stagecoach (1939), Rio Grande (1950), and The Searchers (1956) among many others. Perhaps more than any other filmmaker, Ford forged the legendary screen persona of John Wayne. Like Hathaway, Ford found the Cinerama process difficult. The high fidelity and huge panorama of the image meant that exteriors created artificially on soundstages looked fake and theatrical, but shooting on location was cumbersome and night scenes required large amounts of light to get enough exposure on the three cameras.

The third director, George Marshall, took on the “Railroads” segment. Marshall was primarily known for comedies, particularly the work of Laurell & Hardy, but his career stretched back to 1916 and he was more than capable of handling the downbeat tone of his section, which required special co-operation from a state park in South Dakota to provide a herd of buffalo for the incredible stampede sequence. Of the three directors, Marshall took the assignment in stride – adopting the attitude that a director must adapt and change with the times or risk obsolescence.

The huge scope and long shooting schedule of the project meant that it's all-star cast went through several iterations before it settled into place. Bing Crosby and Irene Dunne were originally intended to star, given that the two of them had developed the project in the first place, but as time went on Crosby had to shift to merely narrating the massive film. Spencer Tracy and John Wayne were to play Civil War generals Ulysses S. Grant and William Sherman but eventually Tracy would drop out and become the film's narrator, replacing Crosby.

The final cast includes Hollywood stalwarts and some notable up-and-comers. One of the biggest challenges is that some of the actors, notably Carroll Baker, Debbie Reynolds, and George Peppard, had to play their roles across a large age range. Jimmy Stewart stars in a role written for Gary Cooper, though Stewart felt he was miscast given that he was in his mid-fifties and his character was romancing a twenty-year-old girl played by Carroll Baker who was thirty years old. Stewart's career in Hollywood stretched back almost as long as some of the directors, while Baker was an ingenue who had been setting the screen ablaze through the later half of the 1950s.

Debbie Reynolds plays Baker's sister, and carries her character through the longest range of ages, from a young girl to a matronly woman. Along the way she also sings three songs in performances that contribute to the film's multi-genre family friendly appeal. Her love interest is played by Gregory Peck, in a year that also saw him starring in Cape Fear and his career defining role in To Kill a Mockingbird (1962).

The film's cast is stacked with notable names, including Henry Fonda in a character role that played against his usual handsome type, and early appearances of both Lee Van Cleef and Eli Wallach, who would come to define a new breed of Western villain as the decade went on. Richard Widmark, best known as the psychotic killer Tommy Udo in Kiss of Death (1947) lends his villainy to the “Railroads” segment, while television stars Lee J. Cobb (The Virginian) and Carolyn Jones (The Addams Family) lend their stability to the action packed “Outlaws” segment. Other notable names include Agnes Moorehead, Robert Preston, Harry Morgan, Russ Tamblyn, Raymond Massey, Richard Widmark, and a blink-and-you'll-miss-him appearance from a very young Harry Dean Stanton.

The picture shot on location in natural landscapes across the United States, a huge undertaking that also involved a higher degree of craftsmanship for the sets and costumes than was usual at the time. The Cinerama cameras made machine stitching too obvious, and so every costume had to be sewn by hand. Filming stretched on to January of 1962, with the film's price tag coming close to $15 million. The film's score was composed by Alfred Newman, one of the greatest composers of the Golden Age of Hollywood, a nine time Academy Award winner whose epic scores include Wuthering Heights (1939), The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939), The Mark of Zorro (1940), How Green Was My Valley (1940), and All About Eve (1950). The soundtrack incoporates a number of traditional songs, sung largely by Debbie Reynolds, including “A Home in the Meadow”, with lyrics by Sammy Cahn set to the tune of “Greensleeves.”

Ultimately, How the West Was Won is an epic presentation of a number of crowd pleasing Western clichés wrapped around a number of show stopping action setpieces. The film's presentation of American history follows a “Manifest Destiny” approach that was considered mainstream and inoffensive at the time. In this view of history, the march of progress had tragic elements such as the destruction of the natural world and the slaughter and relocation of Indigenous peoples, but is ultimately seen as an overall good for leading to the modern nation of the United States. In 1962, during the “Camelot” period of the Kennedy White House, American culture at large projected to the world an optimistic and positive image of itself, one that had yet to be seriously confronted with the counterculture revisionism that would explode in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, Watergate, and the slow erosion of traditional white settler narratives of history.

At the time, in 1962, the gambit of a large scale three-hour epic about the settling of the American west paid off for MGM. How the West Was Won ran in Cinerama theatres for three years, garnered a hugely positive critical reception, and grossed over $50 million. The film's screenplay won an Academy Award, as did its editing and sound. And after years of substandard TV and home video prints that rendered the film something of an ugly mess in an attempt to display the three-panel Cinerama on small flat television screens, the movie's latest Blu-ray release includes not only a beautiful digitally restored version of the film in a “flat” letterboxed version, but also a special “Smilebox” rendition that aims to replicate the effect of the curved screen on a flat surface. However, it is impossible to truly appreciate the spectacle that the film represented in its time without seeing it in a theatrical setting on a curved screen, and so it is with great pride and excitement that the Calgary Cinematheque presents How the West Was Won in a recreation of its original presentation at the Centennial Planetarium Dome, in partnership with Contemporary Calgary.

Written by Ben Rowe.